Japan is a linguistically and culturally extremely homogenous country. Of its 127 million inhabitants about 98.5% are ethnic Japanese, 0.5% are Korean and 0.4 are Chinese – leaving a whopping 0.6% others; including yours truly. Those 0.6% “others” include about 210.000 Filipinos, mostly of Japanese descent, and 210.000 Brazilians, also mostly of Japanese descent – which means that only about 0.3% of Japan’s population are neither Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Filipino-Japanese nor Brazilian-Japanese.

I’m sure you’ve heard the term gaijin before (外 gai = outside, 人 jin = person), a short version of the term gaikokujin (外国gaikoku = foreign country, 人 jin = person). People are still arguing if it’s pejorative term, but personally I don’t like it very much, because it’s such a simple term, pushing everybody who is not Japanese to the outside – which is a precarious thing in a country where a group is still so much more important than an individual.

Integration?

Becoming a foreigner in Japan is actually an achievement by itself. Japan isn’t eager to let many people in and therefore the requirements to get a long-term visa are rather high – usually you have to have either a Bachelor’s degree or several years of work experience; in both cases an employer has to vouch for you. Other possibilities are investor visas or some kind of artist visa, but there quite a bit of cash is involved; and so is with the spousal visa… 😉

Once in the country the Japanese government couldn’t care less about you as long as you renew your visa when it expires and pay your taxes – and those are usually handled by the company you work for anyway. While there are long and public discussions about integration in European countries there is zip in Japan. Language classes and tests? Bah, humbug! On the other hand you shouldn’t expect anybody to be able to speak English anywhere, despite the huge English school industry in Japan; especially at the immigration office, where you can address the staff in English as much as you want – they’ll always reply in Japanese, even though most of the time they obviously understood what you’ve said…

But Japan in general isn’t set up for integration, probably because of the educational system. You have your childhood friends, you have your high school friends, you have your university friends and you have your work friends – usually four different groups that keep you busy for the rest of your life; with no need to make additional friends at any point; or many opportunities for that matter, like community colleges or sports clubs, both extremely popular in Germany, especially after moving to a new area. (With the result that many foreigners in Japan stick with each other, too – I don’t think I know any foreigner here who has more Japanese than foreign friends; and by that I mean friends, not Facebook acquaintances…)

Xenophobia?

With that few foreigners in the country and that strong of a national identity I am still not sure if Japan is an above average racist country or not. People are definitely more polite in general than let’s say in my home country Germany (sorry guys, but certain things really are better in Zipangu…), especially in everyday service situations like shopping, but I experienced some of the weirdest behavior here, probably because hardly any Japanese school kid has foreign co-pupils, while I went to school with people of Italian, Austrian, Indian, Pakistani, Turkish, Japanese, British, Polish and Bavarian descent – and because the average Japanese person doesn’t think that you can understand what they say.

Sometimes they most likely mean no evil (like that one time when I had a dinner date with a Japanese girl at an Indian restaurant and all of a sudden all the tables around us talked about their oversea vacations, their foreign alibi friends and how great it would be to be able to be fluent in English…), sometimes I’m not sure (remember me *not getting a hotel room after the clerk found out that I’m a foreigner*?) – and sometimes they actually do mean harm. For example that young Japanese couple and their two friends who have beaten a Nepali restaurant owner to death in January 2012; one of them were quoted afterwards “I thought the foreigner had shoved me, so I got angry and kicked him many times.” (Note the use of “foreigner”? I’m sure it was “gaijin” in the original… Not “the man”, or “the Nepali” – “the foreigner”…)

Discrimination

It’s just a completely different mindset regarding foreigners and discrimination in general – and most people don’t even question it, because to them it’s normal. Like most countries Japan has a long history of discrimination. It even went through a time when a social class system with all its downsides was officially established; during the Edo period (1603 to 1868). Back then the burakumin (a.k.a. eta, “an abundance of filth”) were the outcasts and usually connected to jobs dealing with public sanitation or death (butchers, tanners, …), but when the class system was abolished the discrimination didn’t end. More than 100 years later, in 1975, there was a huge scandal when an anti-discrimination organization found out that a company in Osaka sold copies of a handwritten 330-page book listing names and locations of former burakumin settlements. Companies bought that book to compare the listed locations with the addresses of applicants – to prevent them from hiring descendants of burakumin; some famous firms like Daihatsu, Honda, Nissan and Toyota were among those companies… Two generations later the issue finally is no more, instead the average Japanese “discriminist“ focuses on foreigners – and I am so tired of and annoyed by comments about “those dog eating Koreans” or “those Chinese comfort women who try to screw the Japanese state”… (“Comfort women” is a Japanese euphemism for the sex slaves of the Imperial Japanese military in World War 2. While some (Japanese) historians like Ikuhiko Hata claim that there were 20.000 volunteer prostitutes, others found that up to 400.000 women were hired under false pretenses or even kidnapped into “comfort stations” all over Asia; but even the “few” volunteers made a bad choice as about 75% of the comfort women died during the war due to mistreatment and diseases. Shinzo Abe, the current Japanese prime minister, claimed during his first term in 2007 that the Japanese military didn’t keep sex slaves during WW2, although the government admitted to the fact in 1993 after decades of denial!)

New Zealand Village

Despite their share of xenophobia the average Japanese seems to love to travel and is actually interested in experiencing foreign countries; especially non-Asian countries… They barely ever jump all in, backpacking all by themselves – more like group vacations with Japanese speaking travel guides. Or an even safer version: themed parks in Japan! Recently I wrote a vastly popular article about the *Chinese themed park Tenkaen*, but in spring I was able to visit the rather unknown *New Zealand Farm in Hiroshima* and the *New Zealand Village in Yamaguchi*. Even less known, and after more than a thousand words of introduction we finally get to it, is the Shikoku New Zealand Village. It was actually the first of the three I visited, but due to certain circumstances I never got to write about it. (If you missed the articles about the other two New Zealand parks I recommend reading them first for background information…)

I don’t remember how I found out about the Shikoku New Zealand Village, but I’m sure it wasn’t an urbex article, because to the best of my knowledge till that very day nobody has ever written about the place. I remember seeing a photo of the entrance to the parking lot though, with heavy machinery in the background. That was on a Thursday – worried that the place was in the process of being demolished I went there two days later, despite the facts that the weather forecast wasn’t favorable and it took me about 4 hours to get there. And except for the photo and the name I didn’t know anything about the park – not what it was, not when it was closed, not if there was security, not how to get in. You know, the risky kind of exploration…

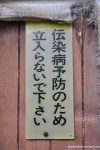

I saw the first surprise when walking up to the parking lot – there was a rather big house right next to it, with wet laundry in the garden. The parking lot was blocked by barricades, entering via a muddy road to the side was difficult due to rusty barbed wire and lots of vegetation. After getting a decent grasp of the situation I decided to jump the blockade at the parking lot and walk right in, my heart pounding like mad. At the time I had more than 150 explorations under my belt, nevertheless I was and still am nervous exploring new and unchartered territory. As soon as I entered the place I heard motor noises… Not a big car motor, probably some gardening tool? Well, after a couple of seconds I realized that it was a model aircraft – and as soon as one landed another one started for almost all of the two and a half hours I spent at the Shikoku New Zealand Village.

Now that you’ve already seen the Tenkaen and the other two New Zealand villages the Shikoku one might not seem that exciting or spectacular, but to me it was the first themed park I ever visited, and I was all by myself, so to me it was extremely adventurous. Cautiously I progressed – first the sheep race track and the archery station, then a barn I wasn’t able to enter. From there I reached a bike race track before I walked back to the main street leading to the Oakland House; basically a restaurant and a souvenir shop. When I walked around the corner I stumbled across surprise number 2: the road in front of me was gone – a landslide washed it away! Now that’s something you don’t see every day… The rest of the park was less spectacular though. Two more barns, a long slide on a slope, a pond, a bakery and a BBQ area.

What was absolutely fantastic about the Shikoku New Zealand Village was the almost complete lack of vandalism. No broken windows, no kicked in doors, no graffiti. Sure, I wasn’t able to enter all the buildings, but that didn’t matter to me, because nothing was bolted up or destroyed – unlike at *Nara Dreamland* for example. Natural decay at its best…

(If you don’t want to miss the latest article you can *follow Abandoned Kansai on Twitter* and *like this blog on Facebook* – and of course there is the *video channel on Youtube*…)

Addendum 2016-01-13: A while after my first exploration of the Shikoku New Zealand Village I revisited this awesome location. *Here is what happened since then.*